Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries

- Reviewed by Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, �첩���� Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, �첩���� Publishing

What are PCL injuries?

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are two tough bands of fibrous tissue that connect the thighbone (femur) and the large bone of the lower leg (tibia) at the knee joint. Together, the ACL and PCL bridge the inside of the knee joint, forming an X pattern that stabilizes the knee against front-to-back and back-to-front forces. In particular, the PCL prevents the lower leg from slipping too far back in relation to the upper leg, especially when the knee is flexed (bent).

|

|

A PCL injury includes a stretch or tear of the ligament. The PCL most often is injured when the front of the knee hits the dashboard during an automobile accident. During sports activities, the PCL also can tear when an athlete falls forward and lands hard on a bent knee, which is common in football, basketball, soccer, and rugby.

Like other types of sprains, PCL injuries are classified according to a traditional grading system.

- Grade I: A mild injury causes only microscopic tears in the ligament. Although these tiny tears can stretch the PCL out of shape, they do not significantly affect the knee's ability to support your weight.

- Grade II (moderate): The PCL is partially torn, and the knee is somewhat unstable, meaning it gives out periodically when you stand, walk or have diagnostic tests.

- Grade III (severe): The PCL is either completely torn or is separated at its end from the bone that it normally anchors, and the knee is more unstable. Because it usually takes a large amount of force to cause a severe PCL injury, patients with Grade III PCL sprains often also have sprains of the ACL or collateral ligaments or other significant knee injuries.

Overall, some degree of PCL damage is common among people who are treated for knee injuries in an emergency department. Athletes have more PCL injuries than any other group, with football players and rugby players having the most and basketball players close behind. Because a mild PCL sprain may not cause pain or movement problems right away, many athletes finish a game after their injury. Some have such mild symptoms that they never seek medical care, and the torn PCL is discovered only when they have diagnostic tests for some other type of knee injury.

Symptoms of PCL injuries

Symptoms of a PCL injury may include:

- mild knee swelling, with or without the knee giving out when you walk or stand, and with or without limitation of motion

- mild pain at the back of the knee that feels worse when you kneel

- pain in the front of the knee when you run or try to slow down (this symptom may begin one to two weeks after the injury, or even later).

Because the first symptoms of a PCL tear may not interfere significantly with an athlete's ability to play sports, many athletes with PCL injuries wait several weeks before they see a doctor. At that first office visit, the athlete may describe vague or nonspecific symptoms — for example, that the injured knee simply doesn't feel "the way it should."

Diagnosing PCL injuries

Your doctor will ask you to describe exactly how you hurt your knee. He or she will want to know whether you had a recent serious impact to the front of your knee, the type of impact (fall, automobile collision), the position of your knee at the time of injury (flexed, extended, twisted), and what symptoms you are having now.

The doctor will examine both of your knees, comparing your injured knee with your uninjured one. During this exam, the doctor will check your injured knee for swelling, deformity, tenderness, fluid inside the knee joint, and discoloration. After determining your knee's range of motion (how far it can move), the doctor will pull against the ligaments to check their strength. You will be asked to bend your knee while the doctor gently pushes forward on your lower leg where it meets the knee. If your PCL is torn, your lower leg can often be moved backward in relation to the knee. The more your lower leg can be moved away from its normal position, the greater the amount of PCL damage and the more unstable your knee.

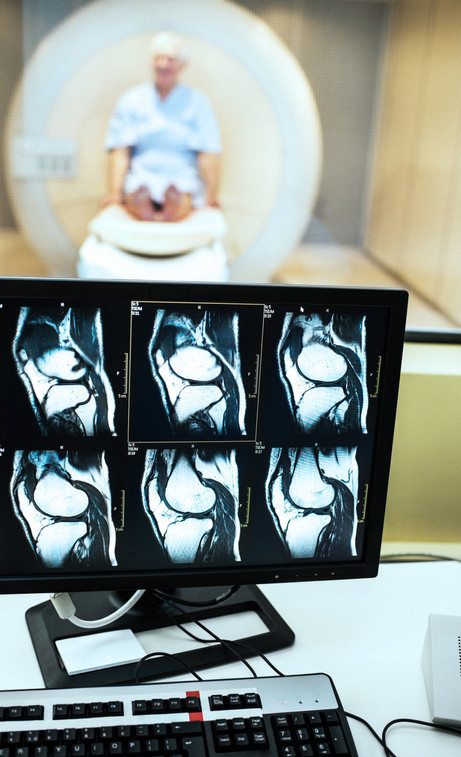

If your symptoms and physical examination suggests you have a PCL injury, you may need special diagnostic tests. These may include standard knee x-rays to check whether the PCL has separated from bone and for other bone damage, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, or camera-guided knee surgery (arthroscopy).

|

|

Expected duration of PCL injuries

How long a PCL injury lasts depends on the severity of your injury, your rehabilitation program, and the types of sports you play. Symptoms from milder sprains may resolve within a few weeks, but it can take a year or more for more severe injuries.

Preventing PCL injuries

To help prevent sports-related knee injuries, you should:

- Warm up and stretch before you participate in athletic activities.

- Exercise to strengthen the leg muscles around your knee.

- Not increase the intensity of your training program suddenly. It's better to increase your intensity gradually.

- Wear comfortable, supportive shoes that fit your feet and fit your sport.

Treating PCL injuries

For all grades of PCL sprains, initial treatment follows the RICE rule:

- Rest the joint.

- Ice the injured area to reduce swelling.

- Compress the swelling with an elastic bandage.

- Elevate the injured area.

Your doctor may also recommend a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin and others), to relieve any mild pain or swelling. After initial treatment with RICE, further treatment of PCL sprains depends on the grade of the injury:

- Grade I and Grade II PCL sprains: Your knee may be splinted in a straight-leg position, and you'll begin a rehabilitation program. This rehabilitation gradually strengthens the muscles around the knee (especially the quadriceps), supports the knee joint, and helps to prevent the knee from being injured again.

- Grade III PCL sprains: Most Grade III PCL sprains do not require surgery, especially if the knee is stable (that is, if there is no significant instability) and symptoms are mild. However, if the PCL has been pulled away from the bone, surgery may be recommended to reattach it with a screw. If the PCL is torn completely, it can be reconstructed surgically using either a piece of your own tissue (autograft) or a piece of donor tissue (allograft). With an autograft, the surgeon typically replaces the torn PCL with part of your own patellar tendon (the tendon below the kneecap) or a section of tendon taken from a large leg muscle. Almost all these surgeries are performed using arthroscopic (camera-guided) knee surgery, which uses smaller incisions and causes less scarring than traditional surgery. After surgery to reconstruct the PCL, you'll wear a long-leg knee brace and gradually begin a rehabilitation program to strengthen the leg muscles around the knee.

Surgery is more likely to be offered to those with Grade III sprains when there are also injuries to nearby ligaments or cartilage.

When to call a professional

If your knee becomes swollen, deformed, painful, or unstable after a significant injury, call your doctor for an urgent evaluation.

If you develop pain at the front of your knee several weeks after you have injured it, make an appointment to see your doctor. Many PCL sprains are overlooked at the time of injury, so you may have sprained your PCL without realizing it.

Prognosis

Most athletes with PCL injuries who are treated without surgery return to their sport at their pre-injury activity level after rehabilitation. For Grade I or II sprains, recovery may be as soon as several weeks to several months. For PCL injuries requiring surgery, full recovery may take a year or more. Recovery tends to be faster and more complete among those who are younger, have good physical function prior to the injury, and closely follow their recommended rehabilitation program.

As a long-term complication, many (but not all) patients with PCL injuries develop osteoarthritis in the injured knee joint, which may develop a decade or more after the initial PCL injury.

Additional info

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS)

National Athletic Trainers' Association

American Physical Therapy Association

About the Reviewer

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, �첩���� Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, �첩���� Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, �첩���� Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.